Superman is Not a Gun

Why The Iron Giant is the best Superman movie.

This is a guest post by Noah Wing. He is a contributing writer for Michigan Enjoyer as well as a teacher at Veritas Scholars Academy. He is finishing an MFA at the Camperdown Writer’s Kiln at New Saint Andrews College.

Like most boys at the age of five, I was scared of what would happen if my Dad died. That scene in The Lion King where Simba creeps toward his dead father and asks him to get up... it terrified me. What would happen if Dad died? I thought. Who would protect us from the bad guys then?

I remember dreaming that maniacal killers, some with clown faces, some with the dead bones of men strapped onto their limbs, would come to kill me as I stood in our entryway. Of course, my parents were chatting in the other room, unaware that a villain was about to murder me. I would cry out to them and they wouldn’t notice me. Maybe I would get their heads to turn and see me in travail. But every time they turned back to conversation as if nothing was the matter.

These fears only plagued me at night, generally when I was sleeping and alone. During the day, my Dad was never going to die or leave me, and I knew that if some psycho with a kitchen knife broke into our house, my Dad would grab the blade, rip it out of the fiend’s hand, even if his own hand bled while doing it. He would tie up the bad guy until the policemen came.

In short, Dad was Superman.

As a boy, I never watched a Superman movie. I watched the quintessential Superman show that has passed on from generation to generation: Max Fleischer’s Superman, which came out in the 1940s.

Each episode, Superman has to save the city from a prehistoric dinosaur that has come back from extinction, apprehend mad scientists trying to steal jewels with armored robots, or save Lois Lane from an oversized gorilla. There is not an ounce of nuance in any of the escapades. There are villains, usually wearing masks, who are clearly evil. Superman always risks everything to save the world, to be good. That never confused me as a boy. Such a story made sense of the world and eased the fears I had when I was alone in bed. When I watched Clark Kent take off that suit and fly off to save Lois Lane from the evils of this world, I knew that everything would be alright.

Outgrowing Superman

Soon, I grew a few years older, and then Batman and The Hulk took hold of my imagination. I wanted to be Batman because of his ingenious gadgets, because of his brooding in a cowl, and I wanted to be the Hulk because he used his strength to channel his anger. Batman and the Hulk had demons, which I thought made them more realistic. I had matured in my tastes. Bruce Wayne lost his parents, and the Hulk was actually a raving madman with no self-control. This was the way the world really was, I thought.

I began to see the silliness of Superman being an overpowered hero wearing a tight-fitting costume. What was the fun of being good at everything, having no broken past, and always winning?

I wasn’t alone in this realization.

Every other nine-year-old boy owned the consensus that Superman was gay. He was boring. Yet, despite my supposed maturity, movies like Superman (1978), Superman Returns (2006), Man of Steel (2014), and James Gunn’s Superman (2025) revealed this property was and is making enough money to keep people coming back for more movies, even if the alien from Krypton is overpowered.

After watching Man of Steel, I wondered what the point of the property was. Was Clark Kent’s Dad really going to sacrifice his life for the family dog ( like every Kansas farmer would)? Was Superman going to smash a trucker’s semi after the guy was mean to him in the bar? Was he going to decimate Metropolis? I liked Superman as a boy, but if Henry Cavill’s Superman was going to take petty vengeance on miscreants, I was out. Even Christopher Reeves’ Superman took vengeance on some bullies in a diner who messed with him.

Whether I articulated what was wrong with this at the time, I knew in my bones something was different about all these adaptations from the Fleischer Superman.

What every Superman movie misses is the American myth of it all. Now that our country is more integrated with people from every ethnicity, Cowboys and Indians have moved into the history books. Superman represents a universal hero for everyone to latch onto in a world of technological advancement. In a world where machine guns, missiles, nuclear bombs, rockets, birth control, IVF, neuro link, and AI exist, Cowboys don’t have the power to face evil the same way.

So what makes this myth sell? It begins with the fears of a boy losing his father. Every boy has not only thought about how his Dad will die, but about how he will die. How we are all going to die. Sometimes in horrible ways.

In the age of the machine, there are many ways to end it all. World War II and Vietnam both revealed the horrors of the atom bomb and Agent Orange. The pill revealed you could die before you’ve been implanted in your mother’s womb. It’s significant Superman came onto the scene in 1938, when the world was on the cusp of the horrors of war and the sexual revolution, because part of Superman’s identity is truth, justice, and the American way. But more importantly, he isn’t a killer. Superman saves the cat in the tree, he talks to the woman who’s about to jump off the top of a building––he doesn’t just fight supervillains. Zach Snyder missed this with his Man of Steel. The whole film is about Superman being a god among men. That’s why Metropolis gets levelled at the end of the film.

Though they have their weaknesses, James Gunn’s Superman and Richard Donner’s Superman both understand our hero needs to save a girl from the building that’s about to fall on her. Yet in the Fleischer Superman, he is always saving life, never taking vengeance or condoning it.

In Superman (2025), Superman has superhero friends who help him defend Metropolis. Gunn juxtaposes the difference between Superman’s mercy and the superhero friends’ willingness to be merciless, sometimes even to kill. Later in the film, Hawkgirl (one of Superman’s friends) hunts down an evil politician, grabs him, and flies up into the sky. The villain pleads for his life, saying, “Superman wouldn’t kill me.” Hawkgirl responds, “I’m not Superman.”

She drops him to his death.

Hence, Gunn doesn’t fully believe in Superman’s ideals. At least he had the decency to keep Superman out of the scene. But most viewers would agree it was distasteful.

So why don’t we all go back to the Fleischer Cartoons? The nihilism of modernity always creeps into our supposedly hopeful American myth anyway.

The Ideal Superman

But maybe the problem with our Superman movies isn’t the nihilism. Maybe the problem is attempting to craft Superman stories with nuance. The beauty of Superman is his simplicity. He loves truth, justice, and the American way. Even though he saves a plane from crashing, he will assure everyone that air travel is one of the safest ways to get around.

Few know this, but there is an ideal Superman movie that packages the Superman myth at an angle while telling an entirely different story about a giant metal robot. Maybe keeping Superman simple is the way to compel viewers.

Brad Bird famously pitched his film The Iron Giant (1999) with a question. What if a gun had a soul and didn’t want to be a gun? The producers greenlighted the project without knowing exactly what was going to come out of it.

Set in 1957, in the small town of Rockwell, Maine, a giant metal robot falls from the sky into the ocean off the coast. It’s the same year as Sputnik. All of smalltown America is worried about the Russians.

And then a nine-year-old boy named Hogarth Hughes finds the metal robot in the woods behind his house and befriends it and hides it in his barn. A government agent reports to the town after hearing reports of colossal bites out of metal objects around Rockwell. After the agent discovers the existence of the robot, Hogarth must protect his new friend from the U.S. Army.

And yes, I’ll explain why this is about Superman.

The iron giant that fell from the sky is the gun with a soul. He cannot remember where he came from. He received a dent on his head after hitting earth and we know he eats metal and is taller than the forests of Maine. After befriending Hogarth, he learns many things about life, as he cannot remember his purpose for coming to Earth. When the two come across a dead deer in the woods, Hogarth explains to the robot that everyone dies and sometimes people use guns to kill. In that moment, the iron giant accepts that killing is bad and saving life is good, revealing he has a conscience.

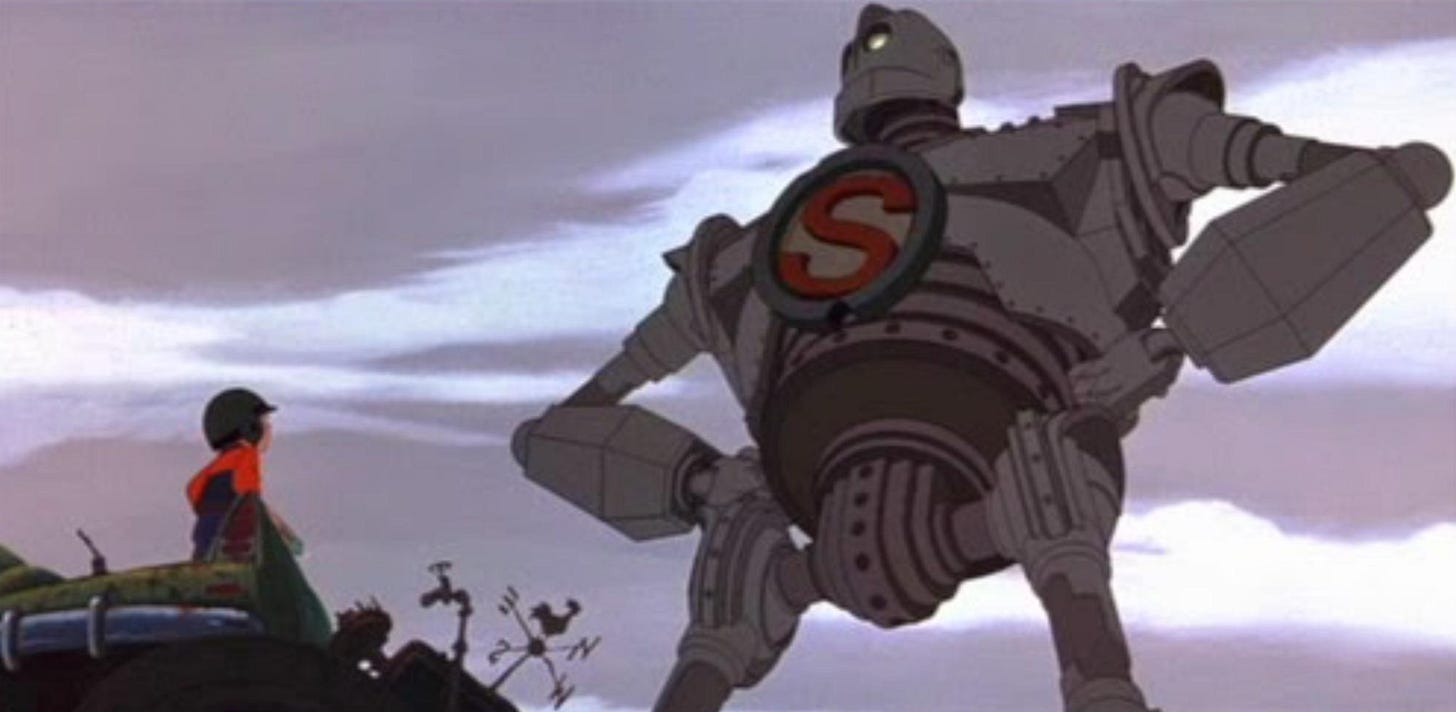

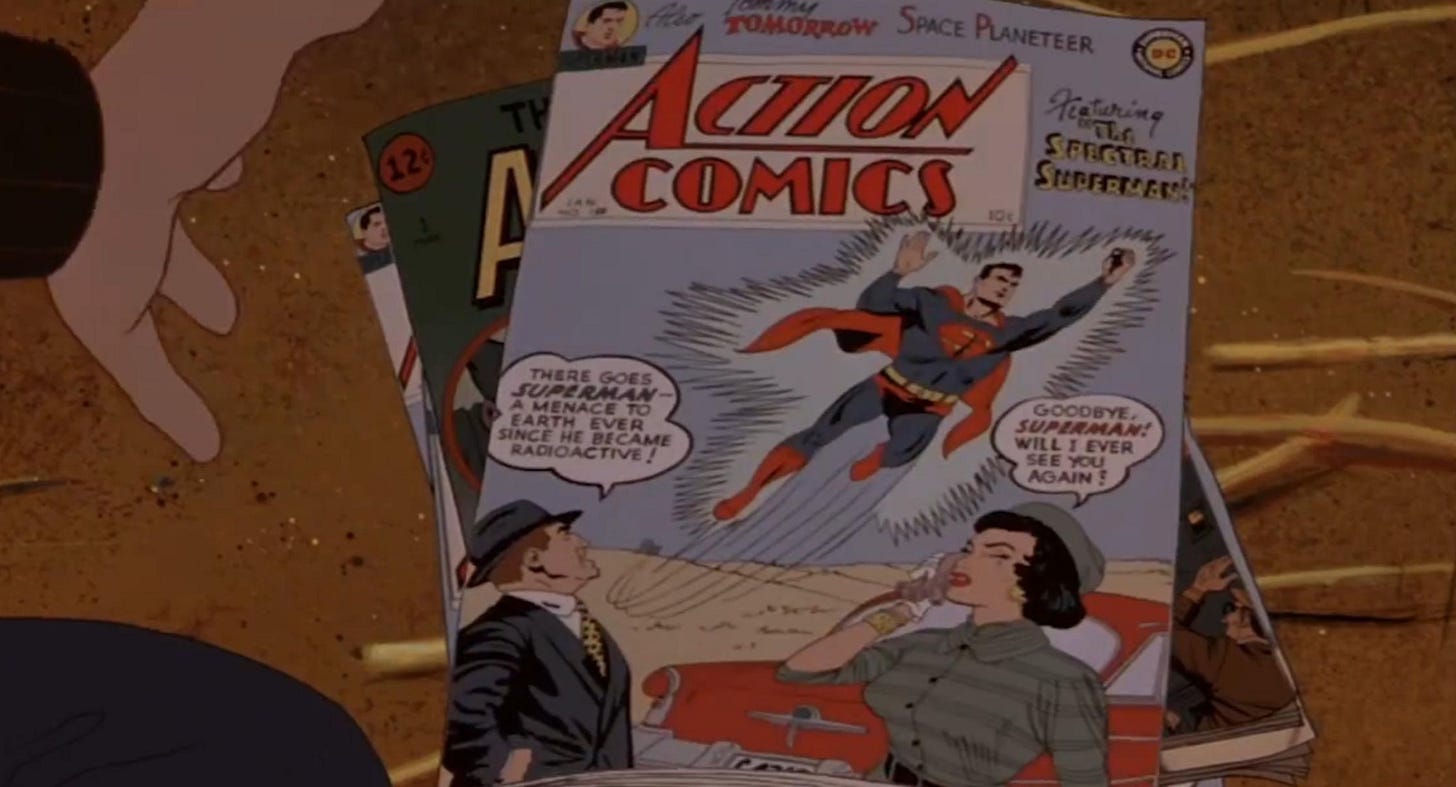

Later, Hogarth brings his comics out to the robot staying in his barn. He first shows him Atomo: The Metal Menace. As viewers, we know nothing about Atomo, but he looks like a typical alien robot invading earth. The metal robot dislikes this, because he remembers that guns kill and Atomo looks like a gun. But then everything changes when we see Hogarth pull out a Superman comic. The boy says, “You’re a good guy...like Superman.” When this happens, the metal robot’s eyes light up and we get no explanation of what Superman does. We simply know he is good. Hogarth doesn't even say Superman saves people instead of killing them like Atomo, because we all know the American Myth that is Superman, the hero that is simply good and saves people. Even if it is a fantasy, we imagine in our worst moments, when the house is in flames and caving in on us, Superman will be there.

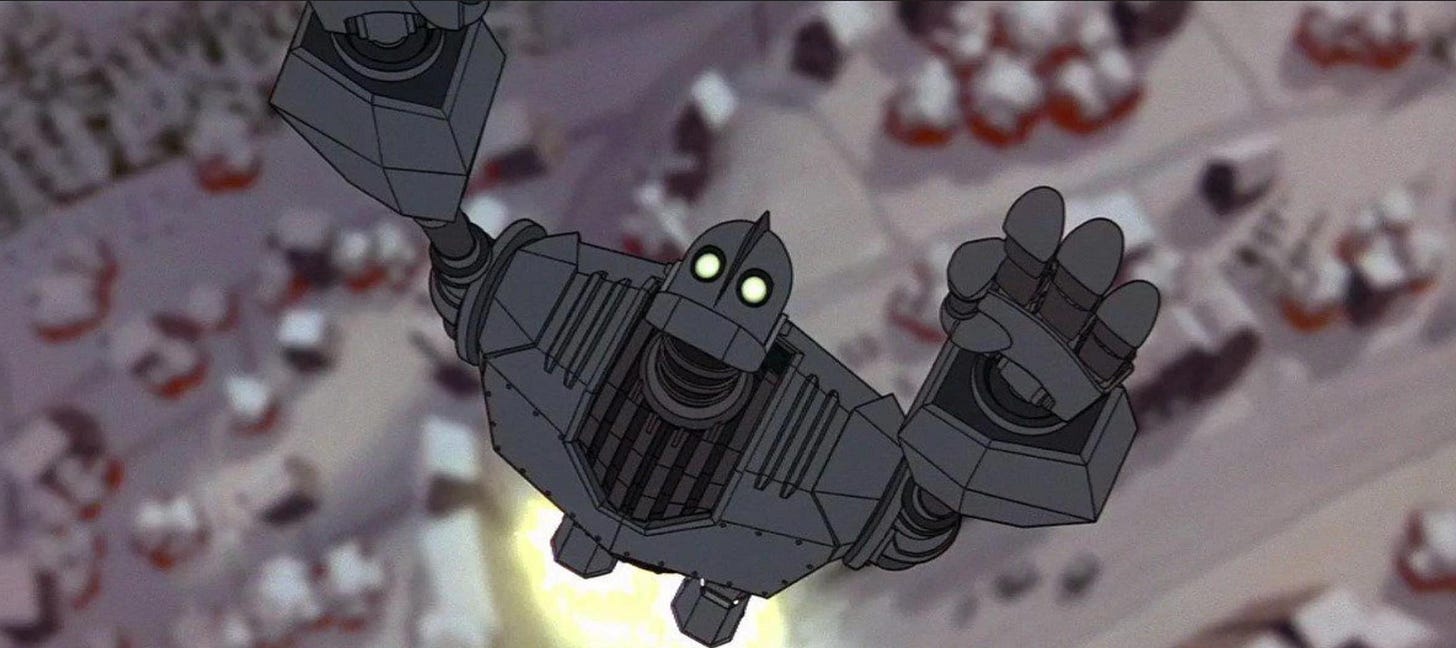

The Iron Giant feels turmoil within him. Sometimes he wants to be a gun, but he must overcome it to become Superman at the end of the film, saving Rockwell from a nuclear bomb.

Unlike the traditional Superman movie, Brad Bird’s Superman is an ideal, something for the iron giant to live up to. The giant knows that it is bad for him to turn into a gun and to kill, and he longs to give himself up as a selfless hero who will save everyone’s life. The iron giant comprehends that he can’t be weak. He has to be Superman or else everyone is going to die.

But as I’ve said before, as a boy I was scared my Dad would die. I longed to feel safe knowing my Dad would never die. In our introduction to Hogarth, the film reveals that his Mom works overtime at a diner while he watches horror movies at home. He’s alone, and his Dad is clearly out of the picture. For all we know, Hogarth’s Dad abandoned him.

Throughout the film, Hogarth wears an old pilot helmet, and we don’t know the story behind it. He wears it every time he is scared, such as the time he finds the giant robot in the woods. Subconsciously, we know there is something important about this helmet. In a later scene, we see Hogarth wearing the helmet as he sits on his bed. The camera pans to the clock on his nightstand, and right next to the clock is a picture of a fighter pilot getting into a plane. He has the same helmet.

And then it all comes together in an understated way. The scene with the picture of the pilot is less than a second. But in that second, we can infer that Hogarth’s Dad died as a fighter pilot in the war. His mom is working late shifts trying to make ends meet. We infer she feels guilty because her son has lost his father.

Hogarth is alone.

When he is scared or faces the enemy, he puts on his Dad’s helmet, which represents a hero who died for his country and for his son. Like Superman, Hogarth’s father died trying to save others, which is why Hogarth needs someone to save him. But someone does come, falling out of the sky from another planet to save Hogarth, who is alone and afraid. The giant metal robot shows up and becomes Superman, saving Hogarth and the town of Rockwell.

The Iron Giant leaves Superman untainted, if nothing else. Throughout this film, our superhero helps us to process our longing for good things to happen in a world where everyone dies and man’s heart is utterly wicked.

What are Myths For?

Myths are important because they give us fantasies to help us live righteously in the real world. As a boy, I thought my dad was Superman. But one day I grew up and realized he was really Clark Kent. As I’ve had to forgive him for that, now I have my own sons. I realize that I am Clark Kent raising sons who now see me as Superman. My oldest son is scared of death, and he finds comfort in knowing that there are dragons in this world that need slaying. Even in his fear, he makes sense of his fears through looking to a protector and longing to be one himself one day. And yet, he will have to forgive me for failing to be the ideal Superman.

A myth helps us process our fears in a world where everything does end, everyone does die. But despite all that, the myth reveals to us that nihilism is ultimately wrong and the rain falls on the just and the unjust.

God is good. Sometimes cars crash, houses burn down, bad guys gun down the innocent. Yet just like Superman, we have to be the protectors who catch the car before it drops on civilians. Just because we are really Clark Kent doesn’t give us an excuse to abdicate bearing the weight of the world on our shoulders.

Fantastic article! This is somewhat beside the point, but I highly recommend *Superman: The Animated Series* for another great adaptation. Maybe it’s just something about the smaller scale of animated shorts compared to live-action feature films that lets the creators get into what really makes Superman work.

I can’t watch The Iron Giant without tearing up at the end. I remember when it came out and it was my little brother’s favorite movie. It’s been great to share it with my kids.